|

The

Bien Edition The Project, Quality, Errors and Market Value by Ron Flynn Click here to buy the Audubon Price Guides In 1858 John James Audubon’s youngest son,

John Woodhouse Audubon, undertook a new and ambitious business venture.

The project was to be the first American full sized reissue of his

father’s original (1826-38) Birds of America. The publication

was to cost about half the price of the original Birds of America,

and was also sold by subscription. The publication was to be issued in

44 separate parts. Each part would consist of seven sheets or pages,

containing 10 images. Four of the sheets in each part contained one

large or medium sized image, and three sheets in each part contained two

smaller images. With the advances in color printing, at the

time, it was decided that the plates would be produced using the very

latest techniques in chromolithography. The firm of Roe Lockwood and Son

of New York was hired as publisher. Julius Bien of New York, a pioneer

in chromolithography, was contracted as the lithographer. The name Bien

Edition, of course, is a credit to Julius Bien. J.W. Audubon’s mother,

Lucy Bakewell Audubon, co-signed some of the business agreements.

J.W.’s older brother, Victor Gifford Audubon, was unable to offer much

assistance to the project, as he was an invalid at the time and died in

1860. The undertaking had problems from the beginning. The Audubons were

still trying to collect monies owed them from the octavo editions,

payment receipts from new subscribers to the Bien Edition were slow in

coming, and unscrupulous dealings of certain business partners resulted

in the tenuous financial condition of the project. Finally, the Audubons

were cutoff from their Southern subscribers at the onset of the Civil

War, and this ended production of the Bien Edition. This huge financial

catastrophe brought near financial ruin to the Audubon family, and

certainly contributed to the death of J.W. Audubon in 1862. In 1863,

Lucy Audubon had to sell family assets, including JJA’s original

paintings for Birds of America, to keep the family solvent.

When production was stopped on the Bien Edition,

only 15 parts had been issued. The 15 parts produced 105 sheets or

pages, with a total of 150 images (under the format described above).

The Bien Edition consists of only one bound volume. It is not known

exactly how many sets of the original 15 parts were printed. The

consensus seems to be that between 75-100 sets were printed, and either

bound into single volumes or left unbound. Early researchers put the

number of surviving bound volumes at 15-23. However, in 1976 Waldemar

Fries had located and catalogued 49 original bound volumes of the Bien

Edition. While individual plates and original bound volumes of the Bien

Edition are rarer, in terms of numbers, than the Havell Edition of Birds

of America, they do not bring near the prices that the Havells do. A HYBRID EDITION – The 1971-72 Audubon Amsterdam Edition, in which

an original Havell Edition of Birds of America was actually

photographed and precisely reproduced using color photo-lithography, is

the first true full size facsimile reproduction of the Havell Edition of

Birds of America. The Bien Edition, however, is not a true

replica of the Havell Edition, and could be called a HYBRID EDITION of

both the Havell and Royal Octavo Editions of Birds of America.

There are a number of differences between the Bien and Havell Editions. The major noticeable difference, from the Havell

Edition, is the page layout system for the Bien Edition. Of the 105

total pages completed and issued in the Bien Edition, 60 of those pages

contain a single species of large or medium sized bird. The remaining 45

issued pages have 2 images per sheet or page (these pages will be

illustrated and discussed below). The part numbers of the Bien Edition

are unique and reflect the issuance of 15 parts, with 7 sheets per part,

and 10 images per part. The bird images and nomenclature on each Bien

sheet came from the Havell Edition prints, while the plate #s used in

the Bien Edition follow, and are from, the Royal Octavo Editions.

However, some birds’ names were changed between the Havell and Royal

Octavo Editions. Therefore, the bird’s name and plate #, on a few Bien

prints, will not exactly match the Royal Octavo Editions plate # list or

image. Other errors in part # and plate # labeling occurred in the

printing of the Bien Edition, and will be noted in the Index Table

below. Probably the most confusing error in the Bien Edition is Plate

#88, the Children’s Warbler (named not for little boys and girls, but

for Audubon’s friend John George Children). The image, and bird’s

name and nomenclature, are from Havell plate #35. However, J.J. Audubon

later realized that his Havell Children’s Warblers were actually the

female and young of the Yellow Poll Wood Warbler. If you then refer to

the Royal Octavo Edition plate #88, you will find it labeled Yellow Poll

Wood Warbler, and the image does not match the image in Bien plate #88.

In fact, the image is unique to the Royal Octavo Editions, and is not

found in the Havell Edition. The vast majority of images and plate #s in

the Bien Edition will generally match the images (with many minor

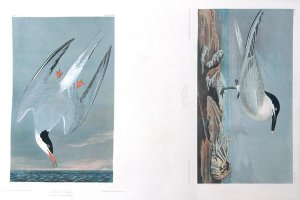

changes) and plate #s in the Royal Octavo Editions. Julius Bien transferred the images from the

actual copper plates, used in the Havell Edition, to lithographic stones

for the Bien Edition. However, changes were made to a number of the

lithographic stones prior to printing. A number of Bien plates were

printed with a colored background tint, similar to that on 2nd and later

editions of the Royal Octavo birds. Many Bien plates had backgrounds

added or changed in various ways from that of the original Havell

Edition. Most of these background changes were minor in nature, but some

were striking and changed the overall appearance of the print.

Several of the small single bird figures in the Havell Edition

were grouped in the Bien Edition. FULL SHEETS AND HALF PAGES – The Bien Edition was printed on sheets of

unwatermarked paper measuring about 26-1/2” x 39” (slightly smaller

when bound into a volume). Up to six different stones, each for a

different color, were used for the printing of each sheet. After

printing, some sheets were finished, or touched up, with a little hand

coloring using watercolor paints. Each sheet was dated either 1858 or

1859 or 1860. A part number

was printed in the upper left above each image, and a plate number was

printed in the upper right above each image. The bird’s name and

nomenclature was generally printed centrally below each image. There is

a single Audubon credit on each sheet, whether it is a single or

two-image sheet. The Audubon credit is at the lower left corner of each

sheet, and reads “Drawn from nature by J.J. Audubon F.R.S.F.L.S.”

There is a single Bien credit on each sheet, whether it is a single or

two-image sheet. The Bien credit is at the lower right corner of each

sheet and reads “Chromolith by J. Bien, New York (followed by the

year).” 45 of the 105 sheets of the Bien edition have 2

images per page. Some

sheets have 2 horizontal images, and some have 2 vertical images, and

sheet #26 has one of each (see the Index Table below). On the

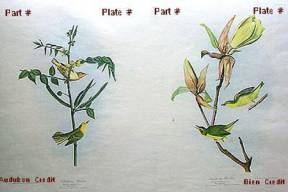

illustrations below, I have superimposed where the part #, plate #,

Audubon Credit, and Bien Credit are located on each sheet. Unbound

sheets, with 2 images, were often cut in half to use smaller frames, or

to frame just one favorite image.

Figure

A shows Bien Edition sheet

6. On the left is Part 1-8, Plate #88, Children’s Warbler. On the

right is Part 1-7, Plate #74, Kentucky Warbler. Notice at the top of the

sheet, there is a part # and plate # for each image. At the bottom of

the sheet, each image has its own nomenclature, and the Audubon credit

is on the left, and the Bien credit on the right. If this sheet were cut

in half, each image would still have its part # and plate #, plus

nomenclature, but only one of the credits for either Audubon or Bien. Fig.

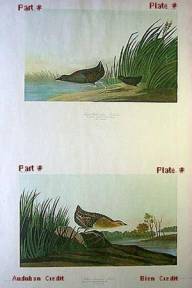

B shows Bien Edition sheet 34. On the top is part 5-7, Plate #308, Least

Water Hen. On the bottom is part 5-8, Plate #308 (error, should be plate

#307), Yellow Breasted Rail. As in Fig. A, each image has its own

nomenclature, part # and plate #. The Audubon and Bien credits are at

the bottom of the sheet. If this sheet were cut in half, the top image

would only have nomenclature plus Part # and Plate #. The top half would

have no credit or authentication for either Audubon or Bien. However,

the bottom half would appear like a small complete Audubon print, with

all identifying information and credits. In

terms of market value, a full sheet should never be cut in half. The

value of the two half sheets would not equal the value of a full sheet.

If Fig. A were cut into half sheets, the value of each half would be

about the same, all else being equal. However, if Fig. B were cut into

two half sheets, the value of the top half sheet (without Audubon or

Bien credits) would be significantly less than the value of the bottom

half sheet.

Photos

by Tom Eckert, courtesy of the Stark Museum of Art, Orange, Texas FACTORS AFFECTING MARKET VALUE – In this Edition, Julius Bien produced some of

the finest examples of large-scale chromolithographic art of the mid

19th century. Still, the science and technology of chromolithography

were certainly not completely refined at the time of the printing of the

Bien Edition. For this reason, the quality and appearance of the

finished prints varied, and that affects the market value of individual

prints today. While the numerous errors in the printing of part and

plate numbers could easily have been caught and corrected by J.W.

Audubon, from proofs supplied by Bien, they do not affect market value.

However, the printing errors, plus other factors, allow one to conclude

that there was a general lack of quality and quality control for the

entire project. Despite the hiring of the renowned Mr. Bien, I don’t

believe that the finished prints that were issued would have received

J.J. Audubon’s wholehearted approval.

If any fault has to be found with the Bien Edition, as we find it

today, it would rest with a perhaps overburdened and under financed John

Woodhouse Audubon. The factors that affect the market value of the Bien

prints today are: supply and demand, print condition, quality and

uniformity of coloring, and the paper used for the prints. Supply and Demand, and Print Condition - Supply and demand determines the general market

value of prints of specific bird species. As with all original Audubon

Editions, the most popular and sought after prints will have a higher

market value. The overall condition of the print is the single most

important factor in determining market value of a single print. It is

quite common to find Bien Edition prints with small marginal chips and

tears or some foxing, but because of the rarity of Bien Edition prints,

these flaws will still have an impact on market value. However, prints

with numerous or more serious flaws and damage will have a much lower

market value. If you go to

my Internet website at www.audubonprices.com

, and click on the banner near the bottom, you can read more about print

condition, and flaws and damage, in some of my published Audubon related

articles. Print Coloring – Pre Civil War chromolithographic prints were

basically still experimental. Two processes, which greatly affected

quality, had not been completely perfected.

Up to six different stones, each with different colored ink, were

used to print one Bien sheet. The colored inks were successively printed

(layered) over each other to produce the correct final colors for each

print. Highly skilled chromists, or perhaps Bien himself, had to hand

mix the various ink colors just right, so that when printed one upon

another, the final result was perfect. It appears that the chromists

experimented or varied ink colors as they went along, and though prints

of the same sheet had color variances, they were all approved and

issued. Therefore, you will find some Bien prints with wonderful

accurate spectacular coloring, while some of the colors in other like

prints might be loud and almost gaudy. You will find some colors in

prints to be dull or thin, and not appear natural or life like. Finally,

some colors, especially in the blues and greens, will not be correct and

will not look right compared to a hand colored Havell or Octavo. The other area of chromolithography that was not

completely perfected was that of color registration. Bien’s people

were pulling the same sheet from as many as six different stones, each

with a different color, to produce the final print. All it took was the

slightest movement or shift of one of the stones, or the slightest

misalignment of the paper on one of the stones, and the result was that

one color in the print did not register (line up exactly) with the other

colors. The result was that the “lines” separating the colors would

appear fuzzy or blurry, and were not sharp. In the fall of 2003, I had the opportunity on

several occasions to examine an original bound volume of the Bien

Edition at a local college library. During the same period, I discussed

the Bien Edition in detail with 5 owners of this Edition (3

institutional and 2 private). We all agreed that the color registration,

and quality of the coloring of the chromolithographic prints, within

given volumes, varied noticeably. However, the differences in coloring

quality and registration were not uniformly unique to specific prints in

the sets. Rather, it is more likely that the coloring of specific prints

varied among different volumes. Prints with bright fresh natural coloring, that

has not faded, will have the highest market value. Some minor

misalignment of color registration should be considered normal, and not

affect market value. Prints with coloring that is faded or off

(unnatural, gaudy, dull, or wrong) will have a reduced market value.

However, print coloring must be considered along with overall print

condition, and condition of the paper, in determining market value. The Bien Edition Paper – A number of writers have commented negatively

about the quality of the paper used in the Bien Edition. J.W. Audubon or

Roe Lockwood, as publisher, could have imported and used J. Whatman

paper. An American made 100% cotton rag paper, such as used for the 1st

Royal Octavo Edition (1840-44), could have been used for the project.

However, a less expensive unwatermarked paper containing wood pulp was

chosen. While the ramifications of using a paper containing wood pulp

was not known at the time, the effect of using this paper has a profound

impact on market value of individual Bien prints today. I persuaded a fellow Audubon collector, who has

a number of Bien half sheets, to make a sacrifice for science. One of

his half sheets had a ¼” chip along one margin. I persuaded him to

trim the print to eliminate the ¼” chip, which would not sacrifice

the integrity of a full size half sheet. The resulting ¼” wide strip

of paper, from an original Bien print, was sent to a local retired

forensic chemist. The chemist performed two inexpensive tests. The Ph of

the sample was tested and found to be 5.4. A Ph reading of 5.4, for

paper, indicates that it is quite acidic. Using a reagent, the paper

sample was tested for lignin. The test was positive, proving that the

Bien Edition paper contained wood pulp, though the percentage of wood

pulp in the paper was undetermined. Lignin is a complex polymer found in

wood pulp, but not in 100% cotton rag. As the lignin breaks down over

time: substances leech out which turn the paper more acidic, darken the

color of the paper, and weaken the fibers of the paper. Because of the

wood pulp in Bien Edition prints: the paper will tear and chip more

easily, become fragile and brittle, and eventually deteriorate and

crumble without restorative measures. A competent paper conservator can

easily save these prints by washing and then deacidifying them, using an

aqueous solution of calcium carbonate or the like. In the Bien volume I examined, I found that the

quality of the paper sheets varied somewhat. Most sheets were uniform,

but did not have the feel or thickness of a Havell or Amsterdam print.

Some sheets were heavier and denser, while other sheets were noticeably

thinner than the majority. I believe that Bien prints that have remained

bound in a volume, or are recently dis-bound, are in generally better

condition than single prints that have been in circulation for some

time. Very few Bien prints, with paper in very good condition are

available today, and those would have a higher market value today. Some

prints on the market may have already been restored. When purchasing a

Bien Edition print, consider the condition of the paper, and the

prospect of having to pay a conservator to restore the sheet before it

deteriorates. Bien

Edition Index Table (in

order by Plate #)

Sheet # - numbers from 1-105 are used as a

reference, and are not found on the Bien prints. Part # - is printed at upper left of each image

on a print. Plate # - is printed at upper right of each

image on a print. The plate # is referenced to the octavo editions, but

there are numerous errors of printing incorrect plate #s on the Bien

prints. Name – Name of bird as printed. Alternate

octavo edition names are found under notations. Notations – Sheet 96, part 14-6, has 3 different birds in

one image. Sheet 49, corrected part #7-10, has 2 different

birds in one image.

Click here to buy the Audubon Price Guides Copyright ©

2008 by Ron Flynn, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED |